Anxiety is a feeling of worry, uneasiness and nervousness that is unpleasant, but an ordinary part of normal experience when we’re faced with uncertainty. Anxiety can also be much more severe, when it is a symptom of an anxiety disorder, such as a phobia (i.e., an irrational fear, and avoidance of some thing or situation). This article focuses on the normal worrying that occasionally gets the better of us all.

Anxiety is a feeling of worry, uneasiness and nervousness that is unpleasant, but an ordinary part of normal experience when we’re faced with uncertainty. Anxiety can also be much more severe, when it is a symptom of an anxiety disorder, such as a phobia (i.e., an irrational fear, and avoidance of some thing or situation). This article focuses on the normal worrying that occasionally gets the better of us all.

Triggers

It is important to understand that anxiety is part of our mind’s activation system, alerting us to something that demands our attention so that we can deal with it. Take a moment to recall a time when you were doing something, such as taking a walk at night, and you heard a sound you didn’t immediately recognize. What happened? First thing is a startle response, alerting you to the presence of something, and prompting your orientation towards it. This is an anxiety response. Next, there is an assessment, judging if the situation is either potentially dangerous or irrelevant to you. Perhaps that noise came from a raccoon, minding its business in the neighbor’s garbage. Immediately you feel a little calmer, and are free to direct your attention. The uncertainty prompting your momentary anxiety response was quickly resolved. The raccoon has been judged as irrelevant, or at least, no “threat,” and the situation did not call for any other action decision from you.

Now let’s change the above scenario just a bit. You are startled by the same noise and turn your focus to where it came from. Instead of a raccoon, it’s a large dog you see. This time, the assessment process takes longer to make a judgment, as you try to evaluate if it’s friendly (irrelevant) or unfriendly (potentially threatening). First, you note its large size—could be dangerous. Second, you see it’s a strange rather than familiar dog—potentially even more threatening. Next, you notice it turn to look at you – no doubt the dog is engaged in a similar process of evaluating you . . . .

While assessing such potentially dangerous situations, you might recall your own experiences in the past of how your nervous system became activated for potential responses. The increased heart rate, heightened sensory activation, the suppression of hunger and fatigue accompanied by the feeling of adrenalin in the system all readying you for “fight or flight.” Judging the situation as a “threat,” a decision-making process about how to respond is initiated. In the scenario described, you likely decide you can and should do something active: you stop, while not turning your back you calmly back away (running can trigger a chase instinct), not making eye contact (which is a challenge) or smiling (baring your teeth is a threat).

After having dealt with the demands of the situation, the anxiety quickly goes away. On reflection, you might notice that during the encounter, you didn’t think about your to-do list for work tomorrow, or other “off task” matters. Your mind was completely focused on the situation at hand.

Traps

The above scenarios illustrate the healthy and adaptive function of anxiety when it alerts us to potential danger and prepares us to respond. Unfortunately, modern life often activates this system in ways that are not productive or adaptive. One way we encounter excessive anxiety (worry) is by getting stuck in the initial threat assessment. Modern life is complex, and with complexity, it becomes more difficult to judge whether a situation is irrelevant or potentially harmful. We can become preoccupied with endlessly evaluating, never gathering enough information to make a judgment needed to move on. We just remain in worried uncertainty.

A second place where we encounter excessive anxiety is where a judgment of “potential danger” has been made, but we choose ineffective control responses that do not deal effectively with the situation. The uncertainty that underpins anxious worry remains intact in these situations. For example, last summer, one of my clients noticed the shingles on her roof had deteriorated, and wondered if they might be leaking—a reasonable assessment of a potential danger: water damage. Her response to the threat, however, was to wait to have her husband look at it, since he “knows about these things.” Unfortunately, he was on assignment over seas, and would not be available even for a discussion about it for several weeks. Her chosen response did nothing to control the situation, leaving her to still to worry about the potential for increasing damage to their home.

Techniques

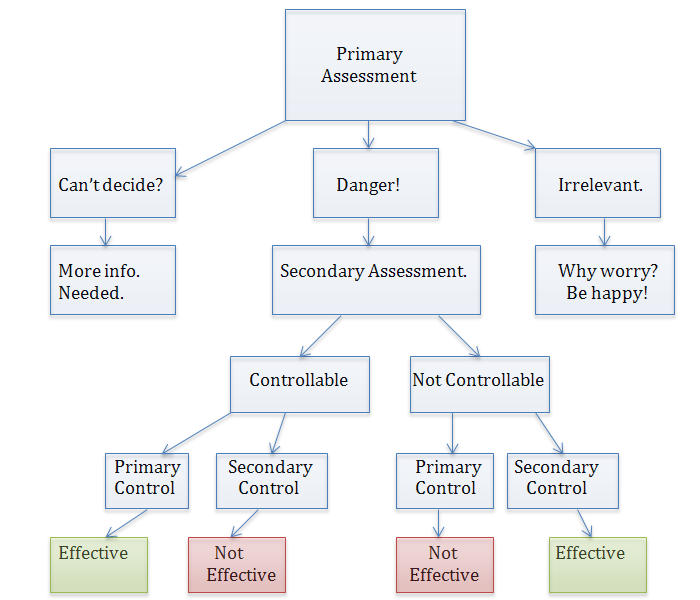

While situation assessment is usually an automatic process of judging the potential for danger, we sometimes get stuck in “analysis paralysis,” and need to manually pull ourselves out of it. Additionally, once we have moved beyond assessment and begin making responses to control, or cope with the situation, we need to evaluate our chosen strategies for effectiveness. Below is a flow-chart model to graphically represent how to think about the anxiety assessment and the control response process. You can use this model to identify where you are stuck and how to break free.

1. Have I assessed, yet, if this is a threat or a danger (Primary Assessment)?

a)Not yet?

What information do I need, or what steps can I take today to make this judgment?

b)Yes, it is not a potential threat or danger.

Anxiety and worry are already going away. If not, go back and re-evaluate.

c)Yes, it is potentially threatening (see Secondary Assessment below).

2. Secondary assessment involves the decision about whether the situation is controllable or not controllable.

3. Control strategies are of two broad types:

Primary control: these are strategies designed to address and change the problem itself.

Secondary control: these strategies we use on ourselves to better tolerate or adapt to a situation.

When dealing with a situation that could be controlled or altered, we do not always choose Primary Control strategies aimed at doing so. Anxiety, unfortunately, will not be reduced by using pacifying, passive Secondary Control strategies (e.g., “I guess I have to grin and bear it”), when there actually is something that can be done.

Where truly nothing can be done, Secondary control strategies are most effective (e.g., Telling oneself “Everyone gets the jitters in these situations, it’s normal, I just need to breath deeply”). What is most distressing, however, is where Primary Control methods are attempted for situations that are not controllable. The so-called “banging your head against a wall” method of trying to do something with no chance of success, increases distress and anxiety, rather than decreasing it. Here, self-soothing Secondary Control methods are needed to help accommodate and adjust to the reality of the situation.

When you notice you are continuing to worry about a situation, evaluate where you are in the model above. Determine whether you have selected Primary, Secondary (or a combination of both) Control strategies to handle the situation. Next, re-assess what aspects of the problem situation are controllable and not controllable, and re-evaluate the wisdom of the control tactics you have chosen. Come up with a plan to implement more Primary techniques for controllable situations, and more Secondary techniques for uncontrollable problems, and see if you don’t begin to feel less anxious almost immediately.

Fell free to contact me to talk about what solutions may be best for you, Ill be glad to help – Contact Form.